INTERVIEW WITH Prof. HIROMASA AMASAKI

Professor at Kyōto University of Art and Design, Department of Environmental Design

Director of Research Center for Japanese Garden Art and Historical Heritage

University of Art and Design, Kyōto

June 9, 2015

Prof. Amasaki, you are head of the research center for Japanese Garden Art and Historical Heritage. This center was founded in 1996 and regularly offers an extraordinary seminar that combines theoretical studies and conventional gardening.

Today we are here to learn about Sakuteiki. As far as we know, this gardening manual was passed on by a poet of the Heian period. Isn’t it peculiar of a poet to write a manual for gardeners?

What, after all, is a gardener? In the Heian period, as well as in the subsequent Kamakura period, the head gardener was a monk. Just because of that, however, one can’t claim: “This is not a gardener.” Monks often were poets while simultaneously being skilled in the art of structuring a garden. The most famous gardens originate from the hands of monks – consider, for instance, Musō Soseki, who landscaped the Moss Garden in Saihō-ji or the Sogenchi Garden in Tenryū-ji (both are temples in Kyōto).

Koke-dera (moss Garden) Saihō-ji Temple, Kyōto

Was Tachibana no Toshitsuna, who is deemed to be the author of the Sakuteiki, actually a monk?

He was a scholar. The gardens looked after by scholars and monks. In the upper class – as for instance with the Gomon, the highest-ranking families of the court nobility – it was common to employ workers of many different occupational groups. What we say today when we mean with “gardener”, in the sense of a landscape architect, has only existed since the 15th century.

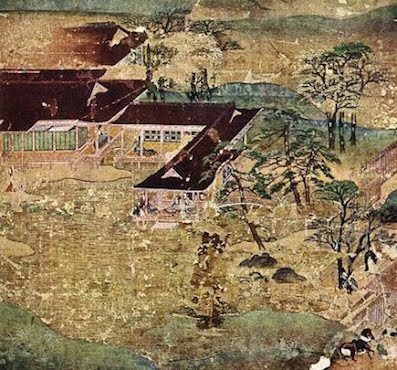

Typical shinden style estate (Heian-Time), with the pond south of the main hall and the stream flowing into the property from the north-east, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum

I had the impression that the Sakuteiki was filled with many rules and several taboos.

There is the rule of communicating with nature, observing it closely and expressing these impressions in the garden. How to do what, however, is not specified.

I think I understand what you are saying. There are many hints in the Sakuteiki that might sound like rules. They are exceptional cases, examples of natural deviation, but they are recommendations – rather than constraints – suggesting not to get stubbornly stuck on a rule. Only by being flexible can one still follow the principle of unison. That is the idea behind it. For example: “A high taki (waterfall) does not necessarily have to be wide.“ Or: “The watercourse doesn’t have to be narrow, as the waterfall is low.” These only seem to be perceptions, but one understands their meaning when seriously observing nature.

Another part states: “Regardless whether it is a stream or something that must be set up, we want to build it in such a way that the water can change direction when it flows and hits a stone!”

On the other hand, it is not like there are no rules at all. How many curves should be built into the slope of the watercourse – this is by all means written in the Sakuteiki.

Thus the Sakuteiki captures that there are rules, but these can be loosely adapted according to the constitution of the location. The most important point of the Sakuteiki is not the indulging of the odds and ends that one must do according to certain guidelines. It is the attitude – the mindset one creates a garden with – that is important. In this regard, people still follow this tradition today because they adopt this attitude.

Garden composition is, by its arrangement alone, very much related to orientation, maybe even a kind of “Guiding”. Are people being guided through the Japanese garden?

A garden invites people; it is more of a playground than an instruction. In the Heian-period, the era of the Sakuteiki, ceremonies were held on a white sand surface (Shirasu) near a pond in the garden. After the ceremony, plays were learnt by heart and recited together. There were games like the one with the sweet iris (Shôbu), which were pulled out of the ground to compare the length of roots. Another game featured little boats floating on the lake, accompanied by music. For this, a stage was built on the middle island (Nakajima), and a band played there.

Today’s form of a leisurely stroll (kaiyû shiki) through the garden is all about the enactment, the surprise of the things one encounters when moving through the garden. For this purpose, landscapes of other places as well as historic sites are mimicked.

Amasaki Hiromasa, Kyōto 2015