INTERVIEW WITH SYUCHI OGUNI, GARDENER

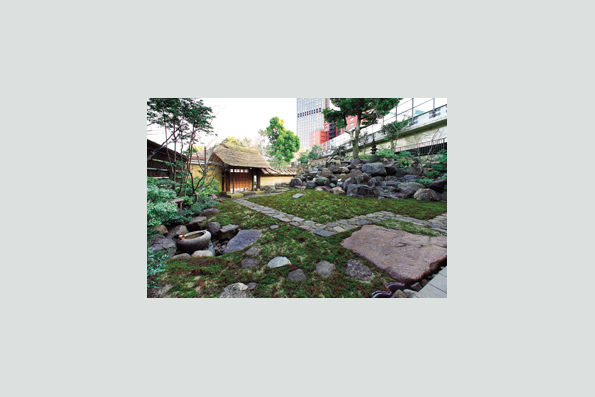

Myojo-in Temple, Minato, Tokyo

June 18th, 2015

Thank you for welcoming us here. We are sitting in the seminary hall of the temple Myojo-in, a side of which is entirely made of glass, allowing one to gaze freely onto the monastery gardens. You designed this garden. Please tell us its story.

Myojo-in Tempel Garden, courtesy: Myojo-in, Tokyo

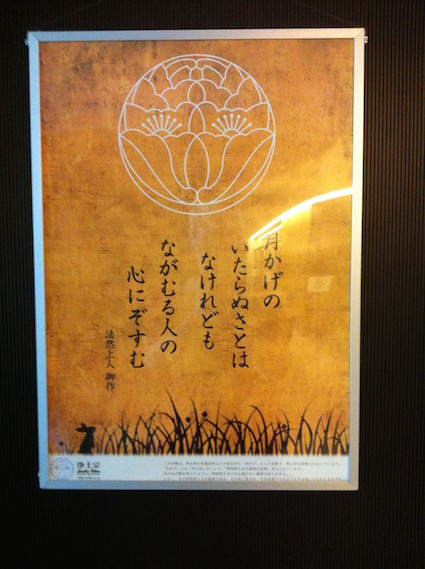

This monastery garden has been here for a long time. I might have laid it out anew, but there already had been a garden at this site: Tsukikage-en. Tsuki means Moon. Hōnen, a poet, wrote a poem named “Tsukikage (月影)”, meaning “Moonshadow”. Here, the Moonshadow metaphorically stands for the ghost of Buddha Amida and his care for us. Hōnen wasn’t just a poet, but also the founder of the Jōdo-school, a form of Buddhism (1). This temple here is part of the Jōdo-school and the garden was conceived according to its principles.

月影の いたらぬ里は なけれども 眺むる人の 心にぞすむ

Tsukikage no itaranu sato wa nakeredomo nagamuru hito no kokoro ni

zosumu.

Though the moon shines all over the world

Leaving no corner in darkness,

Only those who gaze upon the moon

Appreciate its serene light.

Tsukikage no itaranu sato wa nakeredomo nagamuru hito no kokoro ni

zosumu.

Though the moon shines all over the world

Leaving no corner in darkness,

Only those who gaze upon the moon

Appreciate its serene light.

This garden has an upper and lower area. In the Buddhist vision, there are basically two worlds: Shigan, the here and now, and Higan, the other world that lies in the western mountains. There is a term, Shinnyo, which exists between two things, for example between left and right, light and dark, here and there. The term indicates the design of something there, where the border runs between these things, but also where the two things meet. This is shown here in this garden.

The lower part of the garden represents Shigan, otherwise known as our world. Hence, perishable items such as wood were selected here, as these don’t last forever. In the upper part, representing Higan, stones dominate. Such material doesn’t decay. Thus, the materiality itself creates a contrast. A group of stones was set there, with a very large stone at the top, surrounded by 25 other, smaller stones. This sequence of stones in the garden is the translation of an image. The main temple of the Jōdo-School, Chion-in in Kyōto, hosts a Hayaraigō-zu, a painting. The painting depicts the Buddha Amida and his following of 25 Bodhisattvas descending from the mountains of the other world (Higan) in order to retrieve someone recently deceased.

Amida Nijugobosatsu Hayaraikō-zu (The Hayaraigo - Amida and twenty-five Bodhisattvas coming to welcome), National Treasure from Chion-in, Kyōto

Where do these stones come from? And have they been selected for already having a certain dynamic, for already having a movement within them?

Of course “the more slanted, the better” doesn’t apply. Of course the stones have to hold a certain balance and must be in harmony with one another. In Tokyo there aren’t any stones; the ground in Tokyo is composed of different soils, therefore the stones must be brought here from elsewhere. The stone in this garden comes from Tsukuba, from the mountains. But in Japanese landscape gardening it is common to re-use old materials. The same applies for this garden: the square stones far up come from the former cemetery of the temple, for instance.

The old must therefore not necessarily remain in place or disappear, but can be taken to another place and given a new role?

Yes, this is about the characteristics of the stones one must use. One combines old and new materials. One doesn’t create a new garden from completely new materials.

Myojo-in Tempel Garden, Tokyo 2015

Myojo-in Tempel Garden, Tokyo 2015

Oguni Syuchi, Tokyo 2015